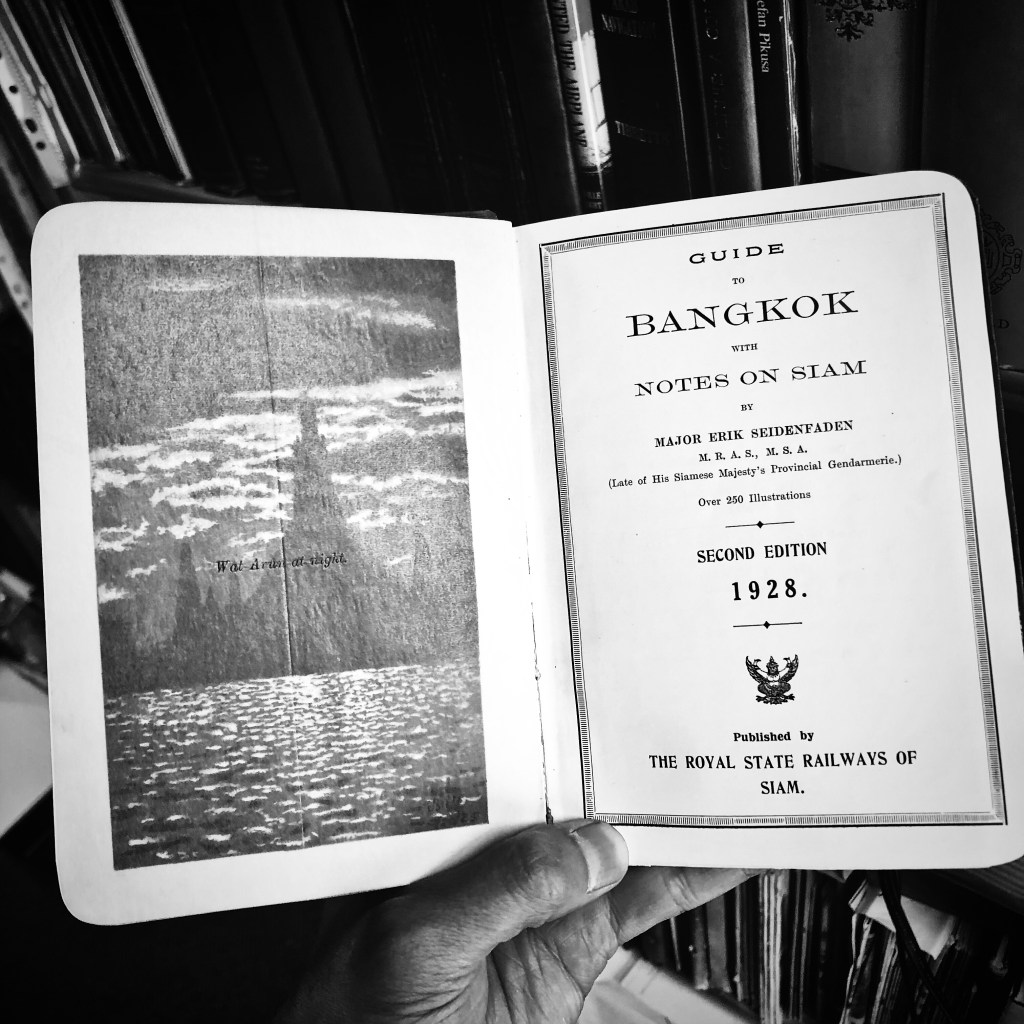

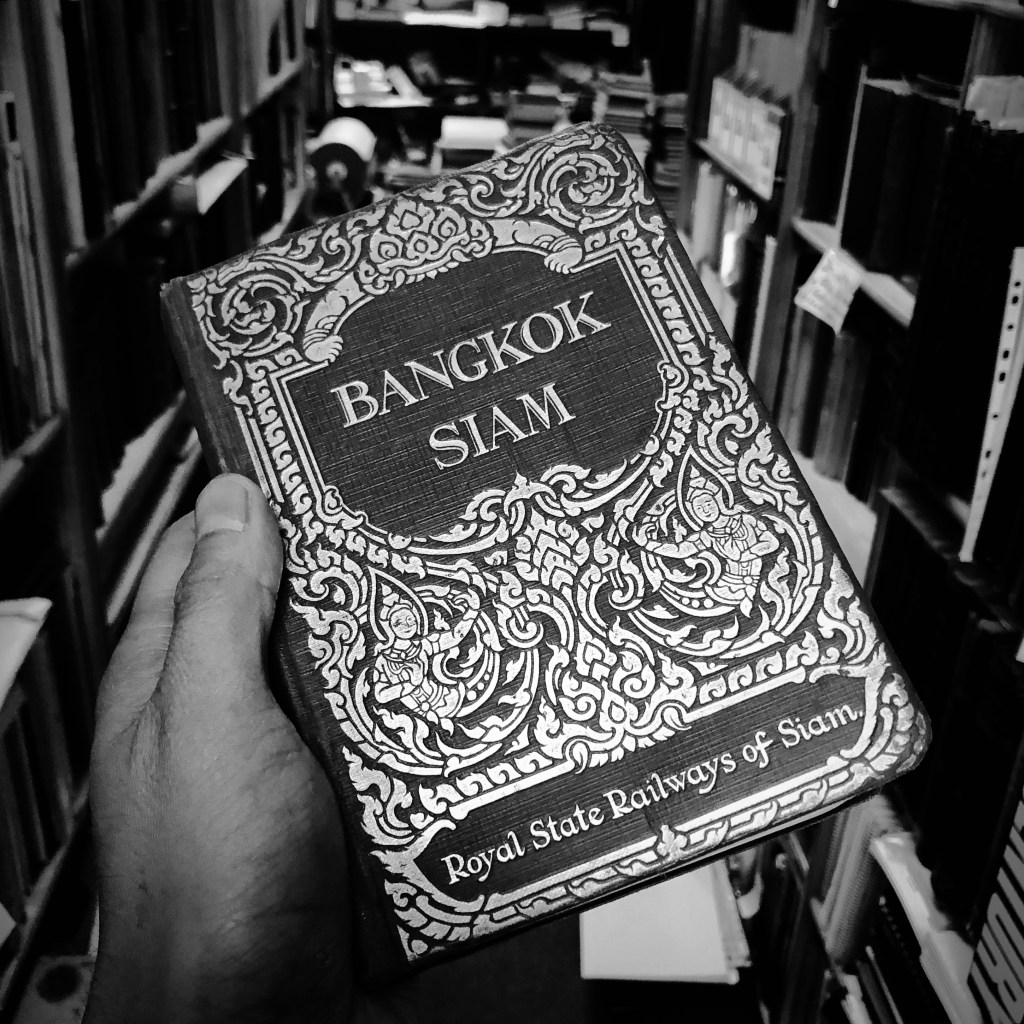

In 2011, I fell under the spell of a Woody Allen film called “Midnight in Paris”, a gorgeously shot cinematic love letter to past and present day Paris, as well as the city of the director’s imagination. In the movie, the protagonist Gil is transported back in time one evening at the stroke of midnight via a vintage Peugeot to the Paris of the Lost Generation, where artistic luminaries lived intertwined lives during the 1920s — a period that inspired a lingering sense of nostalgia that permeates Parisian streets to this day. Years later, while living in Adelaide, Australia, I was gifted a rare gilded relic from Bangkok’s earliest days of modern tourism — Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam, published by the Royal State Railways of Siam, Second Edition, 1928. Like the elegant roadster magically appearing at midnight in Woody Allen’s film, this wondrous publication has served as my own time travel device, inexplicably capable of whisking me back to the Bangkok of the past and of my own imagination, where surprisingly, much of what was written about the city nearly a hundred years ago still survives to this very day.

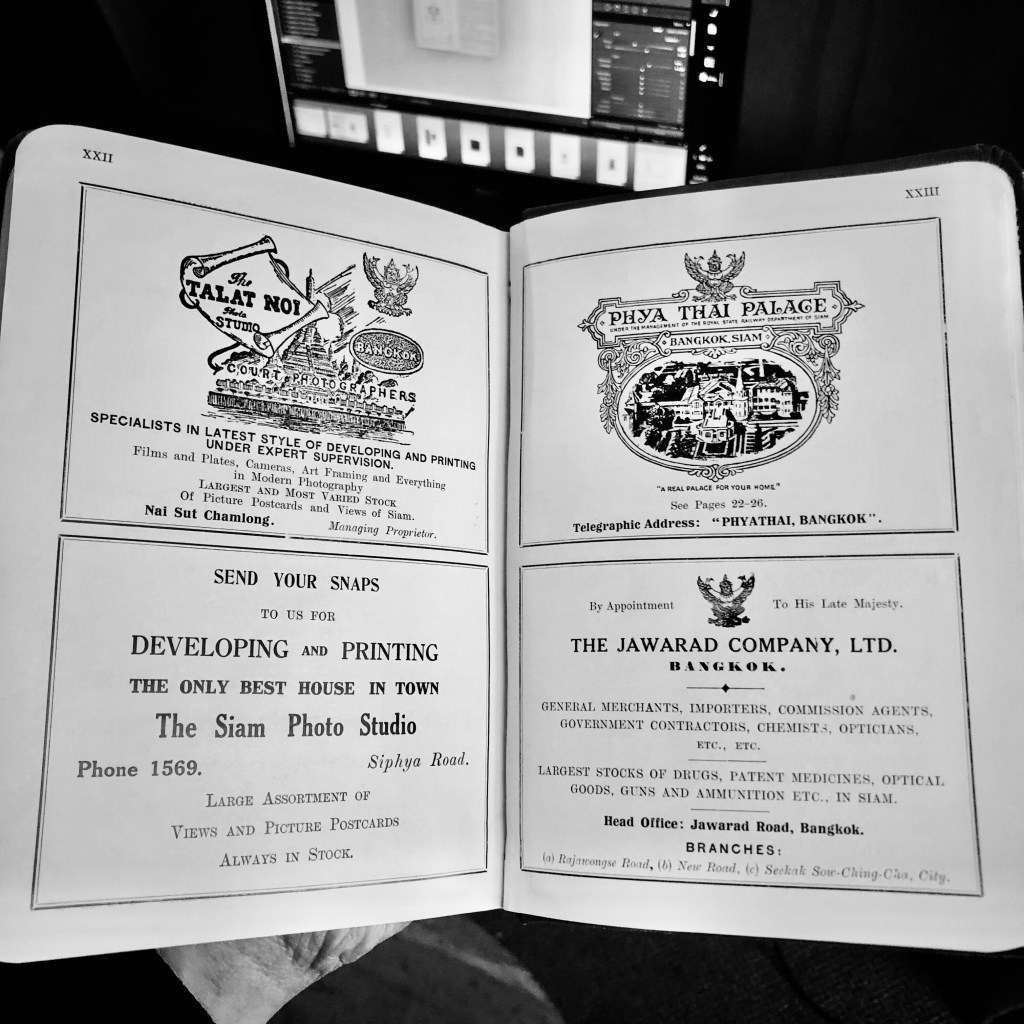

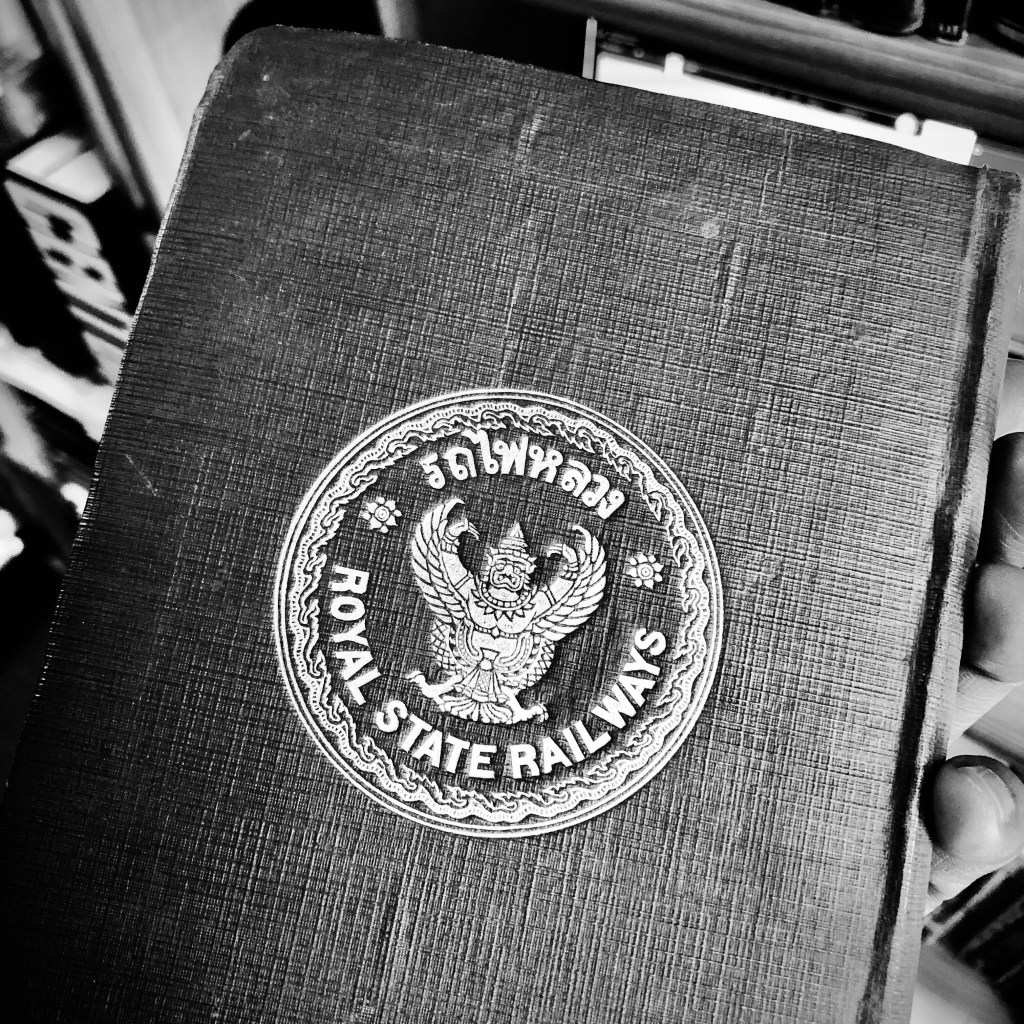

Precious in appearance and feel — with luxurious bindings akin to a book of incantations — everyone who sees this printed work is charmed by its yesteryear appeal. However, beyond the decorative colour plates, maps and half-tone illustrations lovingly executed by the Arts and Craft School of Bangkok (now known as Pohchang Academy of Arts), this antiquarian object reveals the insights and voice of one of Bangkok’s most remarkable expatriates, the dramatically named Danish Major Erik von Seidenfaden (1881–1958), who was commissioned by the State Railways of Siam to write what was at the time, the largest and most comprehensive guide to Bangkok ever attempted. The resulting successful publication would form the template for all subsequent English language guides to Thailand’s capital city. Seidenfaden was a self-styled ethnologist, historian and chronicler of the history, culture and languages of the Thai peoples. A visually dashing man very much of his time and class in terms of outlook and prejudices, Seidenfaden’s curiosity for knowledge would nevertheless lead him to venture far from his small European homeland and ultimately spend over four decades immersing himself in the language and cultural fabric of Siam in a way that few foreigners had ever done before or have since. To read this guidebook, is as close as one can get to the Bangkok of a hundred years ago, described by one of the city’s historical characters, like those from Paris depicted in Allen’s film, but in the context of Thailand — Seidenfaden may not have been an artist, but in my mind he is a person of equal fascination and knowledge who gives his account of Bangkok at the dawning of the golden age of tourism. His work is a contemporary piece of travel writing intended as a guide, told through the words of a foreigner who was not a visitor, but rather a resident who at the time of its publication had already spent more than two decades living and travelling throughout the kingdom.

“A certain amount of courage is needed to bring out a guide book.”

Preface, Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam

Courage indeed. In the 1920s, no comparable English language guide to Bangkok had ever been attempted in scale or in scope and so it fell upon Seidenfaden to put pen to paper — the right man, at the right time, in the right place. In 1906 as a junior lieutenant in the Danish army, he travelled to Siam at the young age of 25 to join the The Royal Siamese Gendarmerie, the country’s provincial military police force, eventually rising to the rank of captain in 1907 and to major in 1914, finally becoming Chief of The Royal Siamese Gendarmerie’s officer school — an institution with a mandate to modernise Siam’s military. Following his retirement from military life in 1920, with over a decade of experience living in numerous provinces throughout the country, he relocated to Bangkok and took a position with the accounting department of the Thai Electric Corporation Limited, Thailand’s first power company. It is during this period when Seidenfaden, who by then was fluent in Thai as well as married to his Thai wife (Khun ‘Mali also known as Maria’ Praivichitr Emdeng, 1892-1973), was approached by the Royal State Railways of Siam to write the content for their ambitious guide project in 1927.

Just as in Paris during the same period, Bangkok in the 1920s bore witness to a decade of prolonged economic growth, artistic freedoms, widespread migration and industrial innovations. Nowhere in Siam was this tide of progress more exemplified than in the country’s capital. In his easy tone, Seidenfaden introduces us to a city transitioning into modernity.

“No other city in Southeastern Asia compares with Bangkok, in the gripping and growing interest which leaves a permanent and fragrant impression on the mind of the visitor. It is difficult to set down in words, precisely whence comes the elusive fascination of Bangkok.”

Chapter 1, How to Reach Bangkok, Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam

Through the words of Seidenfaden, we find ‘a city like no other’, where it is possible to easily transition from the throng of city streets and find oneself easily enough in a residential quarter ‘surrounded by bungalows in a large compound that is tree-covered, green and refreshing’. Beyond the glittering attractions, Seidenfaden takes pains to write that the burgeoning metropolis has more than material charms, that even ‘the most bitter misanthrope cannot but feel that in the very atmosphere of Bangkok, woven into all the stir and briskness of its daily life, is an impelling and pleasurable sense of more than mere contentment’, a city that defies description. Of course in the more than 300 subsequent pages, Seidenfaden works hard to accurately describe as much as he can, all the charms, the intricacies, the exoticness and the rich historical and cultural context of a city and people he had so clearly come to appreciate and understand.

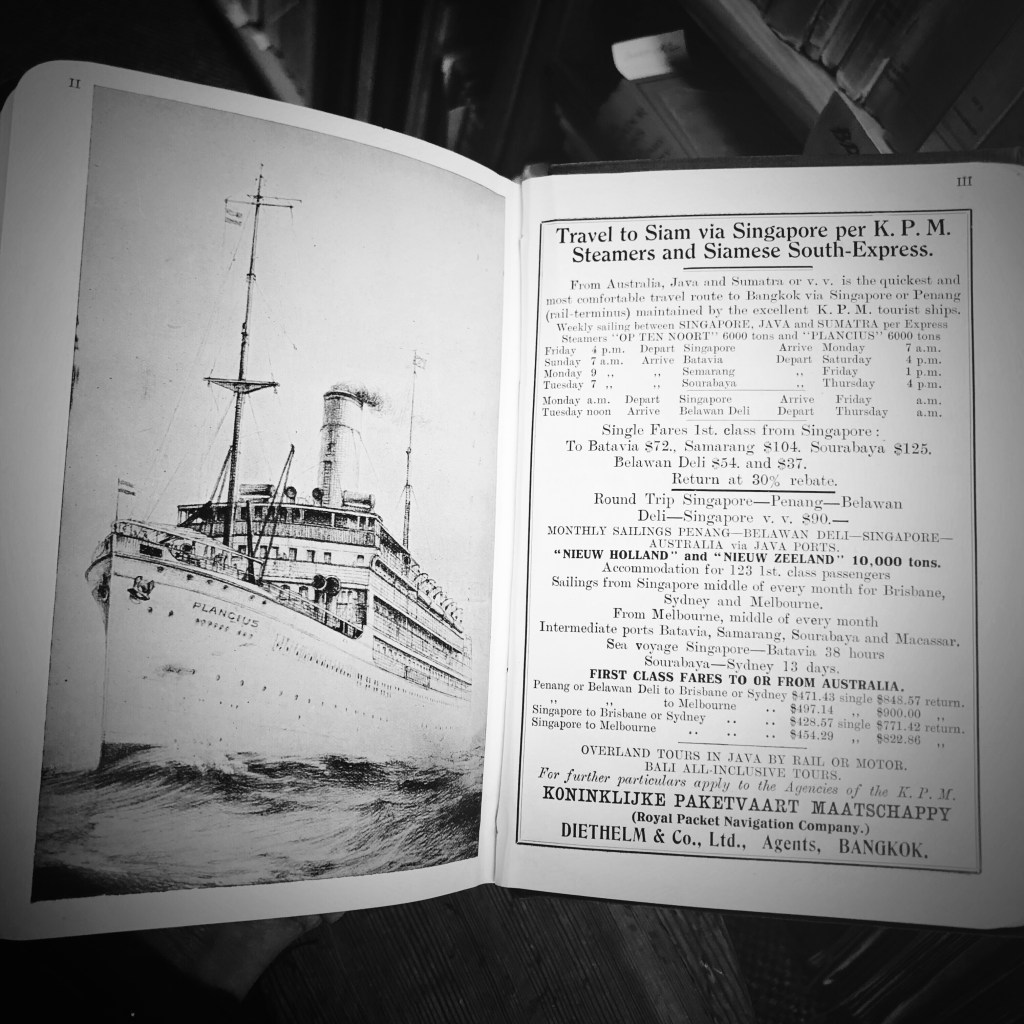

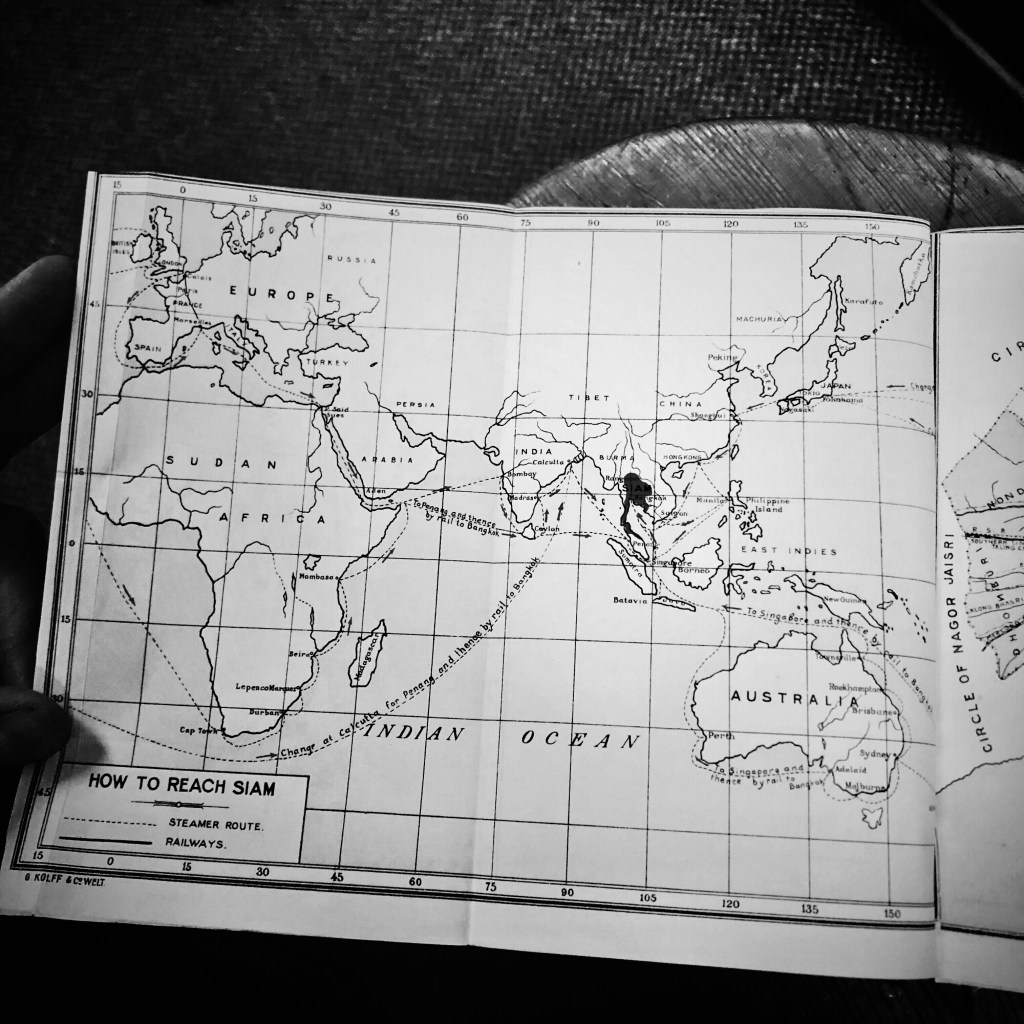

Beyond merely waxing lyrical about the city, the publication is at its core a guide and within its pages are all the necessary elements that constitute such a work. All the logistics of how to reach the city (by steamer and by train as no flight services were yet operational). With regular and ‘irregular’ departures from nearby ports of embarkation such as Penang, Saigon and Singapore, in addition to further ports of call. This being a guide published by the Royal State Railways of Siam, there is particular emphasis on the train routes leading into Bangkok and the convenience, timeliness, reliability and even comfort of the numerous train routes into the country, with ‘the utmost attention given to the sleeping and restaurant car services’. Timetables, rates, currency conversions (One Pound Stirling to Eleven Thai Bath) and connections are well detailed. The guide touts that the scenery ‘along the line which gives the traveller a good impression of both British Malaya and Siam’. The ‘privilege of breaking journey at various interesting points makes it more advantageous to travel by rail’. Hua Hin-on-sea warrants notable mention as a ‘famous seaside resort of Siam, with its excellent golf course’. Even the late Lord Northcliffe is quoted by Seidenfaden as remarking in The Daily Mail: “My principal recollections of the Siamese State Railways are of wonderful smoothness of running, of beautiful scenery, and of one of the most peaceful and comfortable train journeys I can remember. I wonder what Lord Northcliffe would say of today’s current provincial train system in Thailand.

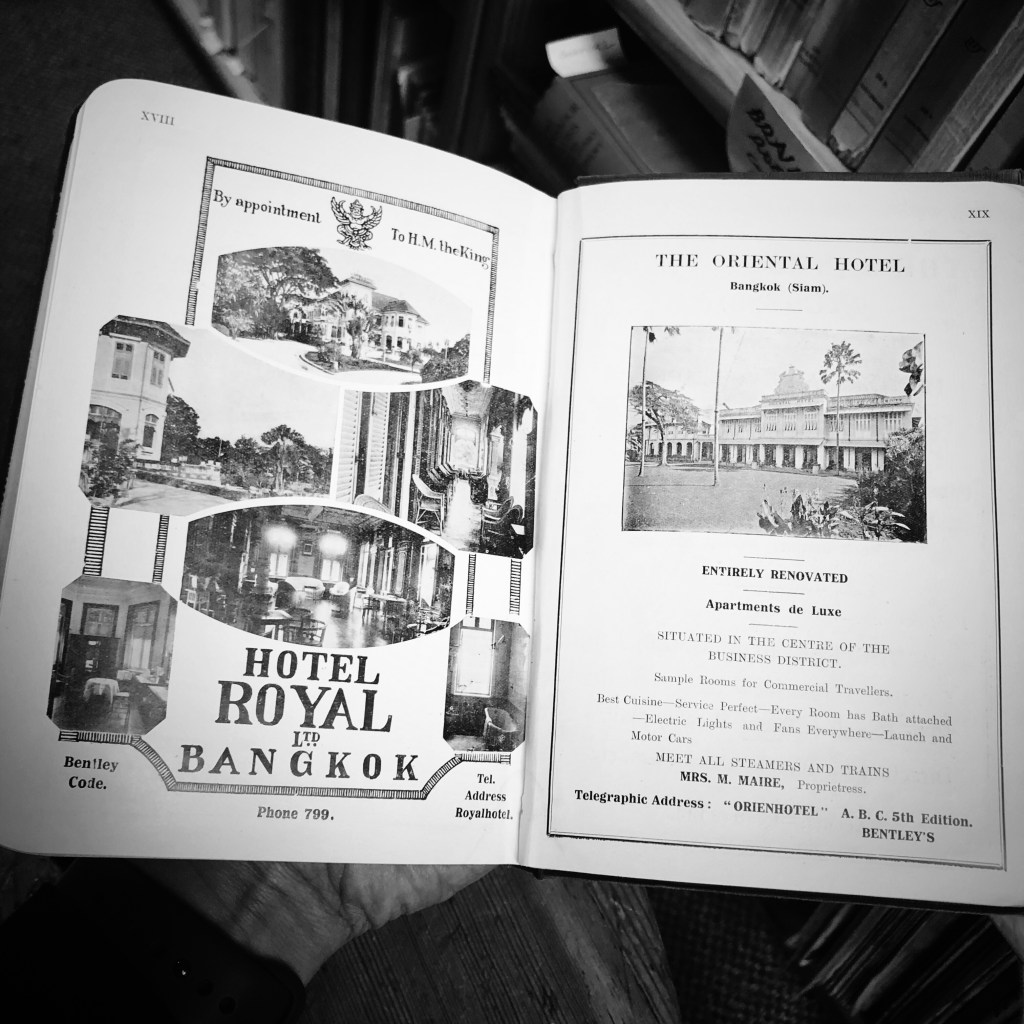

Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam is richly written and devotes a chapter to suggested itinerates for up to seven days visiting Bangkok with a list of attractions as well as many subsequent chapters on the arts, architecture, culture, temples and places of note that for the most part, contain descriptions and context that are largely relevant. But more than that, Seidenfaden condenses a vast amount of information and weaves an entertaining tale of the history of the city, dividing into further sections on describing the key distinct sections of the capital, often in admittedly romanticised tones but he does not shy from descriptions of harsh realities or the prejudices of the day from the perspective of a white European in Bangkok. There are hundreds of illustrations as well as dozens of vintage advertisements and what is so pleasing is how relevant the majority of the content remains even to this day. What is also well written is the end section of the guide entitled ‘Notes on Siam’ where Seidenfaden attempts to provide context on modern day Siam, the developement of the kingdom, its religion, its people, the monarchy, as well as the country’s path forward with modernisation looming all around. Seidenfaden writes sensitively with a confidence that comes from years and years of personal first hand knowledge. Although later in his life, Seidenfaden would go on to publish numerous semi-academic essays and even write a book on Thailand and its ethnography in addition to many papers on archaeology and region’s language ethnic attire, in Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam, we read the words of a man who enthusiastically paints a portrait of a city filled with wonder at the very beginning of a career in writing that would lead to later published works. Seidenfaden’s first major foray into writing in 1927 is relaxed yet informed, his voice is not that of a jaded longtime expatriate, but of a person still enthralled with his adopted home even after two decades, eventually followed by two more decades of residency.

Let’s be honest, most guidebooks are not texts we read from cover to cover, we look at whatever relevant sections we need to and move on. Seidenfaden’s writing carries a more charming tone that kept me moving forward, turning from one page to another. In my own reading and re-reading of Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam in the years I have been in possession of it, I continually find a renewed love of Bangkok.

Since being given the book I have done some more research into the life of Major Seidenfaden, a man who is known well enough in academic, military and diplomatic circles in relation to the history of Thailand, but who has all but now been forgotten in popular culture. I continue to be fascinated by this larger than life character who played a notable role in Thailand during a pivotal period of the country’s development. In the documents that remain in several archives in Thailand and Denmark, you can find glimpses of a man of singleminded determination and who had a strong interest not only in acquiring knowledge, but also in sharing it. One colourful story from his highly decorated military career recalls how in 1907, the then young Captain Seidenfaden was put in charge of an enormous convoy moving the Siamese Governor-general Phraya Chum Abhaiwongse and his entire provincial entourage following the ceding of territory to French Indo-China. This epic cortège included 37 elephants, 26 of them carrying the Governor-general’s 44 concubines and 50 children and numerous court dancers and members of the household. Altogether the convoy journeyed some 300 kilometres west under constant rains consisted of 1,700 ox carts, of which 1,350 were requisitioned from the local farmers of Prachinburi in Siam, their final destination — an event described in details as cinematic as any. A far grander sojourn than Karen Blixen (also a fellow Dane) could have ever imagined following her own famous ox cart mission to bring her husband and the British troops supplies during WWI in Kenya, as described in her novel, Out of Africa. Seidenfaden would eventually be awarded the knighthood of the Siamese Crown Order in 1912, the order of the Crown of Thailand in 1926, the Danish knighthood of Dannebrog, as well as knighted with the Siamese Order of the White Elephant, in 1932. He would go on to become one of the founders of the prestigious Siam Society and would serve as the institution’s last foreign President.

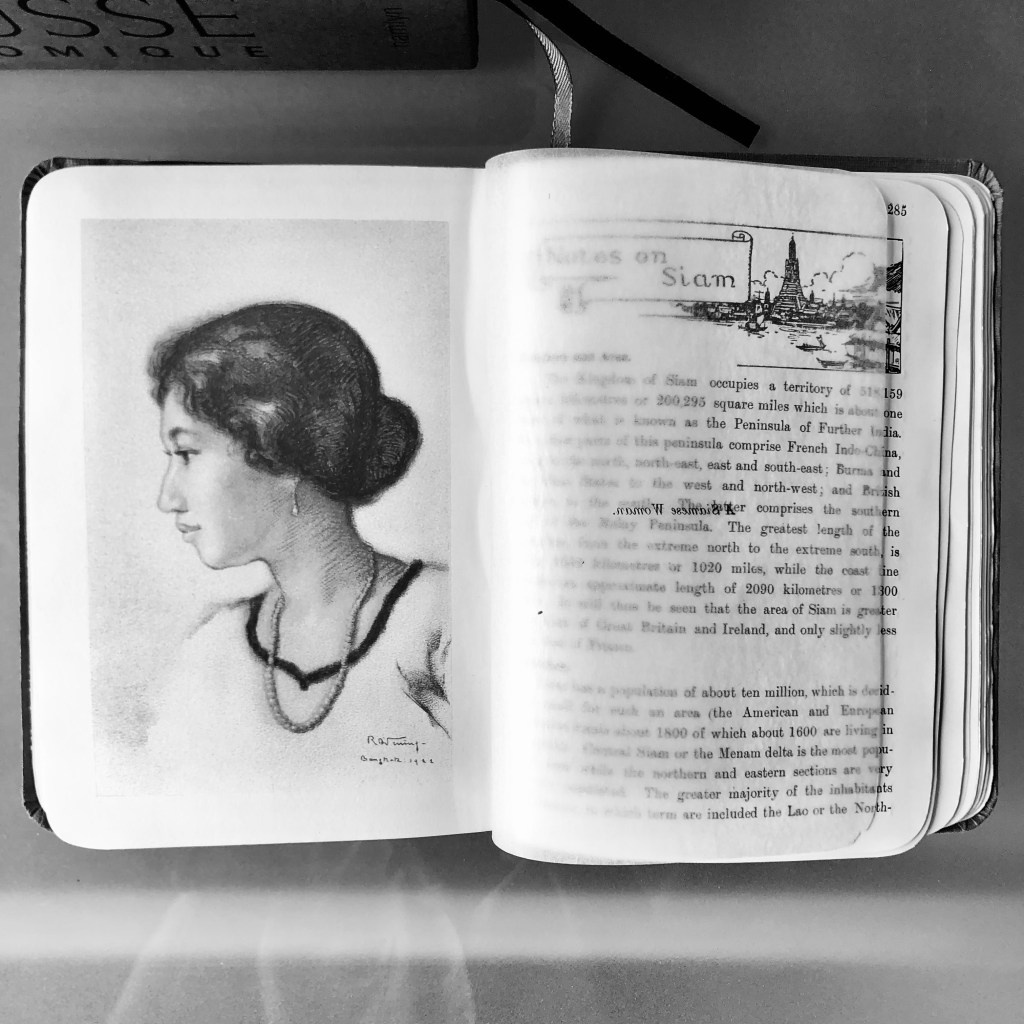

There is one particularly poignant page in Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam that I find myself constantly lingering on and that is sublime colour plate between pages 284 and 285 at the beginning of the chapter ‘Notes on Siam’, with the caption, ‘A Siamese Woman’. This hauntingly elegant image shows a beautiful profile sketch of a thoroughly elegant and modern woman. We do not know who she is based on the information in the guide, but in a paper published in 2022 in the Journal of the Siam Society entitled Erik Seidenfaden and his Quest for Knowledge: Gendarmerie Officer, Amateur Scholar and the Siam Society by Søren Ivarsson and Sing Suwannaki, there is a photograph of Seidenfaden’s wife Mali, which bares a striking resemblance to the colour plate in Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam. Although I do not know for sure, I like to believe that the two images are of the same woman, both she and the words written in the guide reflect a very human side to Seidenfaden. I like to think Seidenfaden intentionally had this image included in the guide to preserve for all time a personal part of him and his passion. He was undoubtedly a man who loved Siam, and I like to believe he loved his wife too — they had six children together and remained together the rest of their lives.

Woody Allen crafted a movie which visually teleported me back to a Paris that was a heady mixture of fact and fiction, to spend time with characters and places from a past both real and imagined. Seidenfaden, through Guide to Bangkok with Notes on Siam, achieved exactly the same effect for me, taking me back in time to my own real and imagined city of the past — one I often return to whenever I want, to my own Midnight in Bangkok.

Guide to Siam with Notes on Siam, Second Edition, 1928

This publication was first published in 1927, followed by a second edition in 1928 and a third edition in 1934. It is currently out of print but still available in numerous private collections including the University of Denmark and the Siam Society.

In 2004, Erik Seidenfaden’s extensive personal library of Thai books was donated by his daughter Grethe Seidenfaden (1929–2012) to The Thai Section, Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen.

131 Soi Sukhumvit 21, Khlong Toei Nuea, Watthana, Bangkok 10110

NOTE: A very special thank you goes out to Mick, Sue and Tom, who gave me one of the most thoughtful gifts I have ever received and with whom I spent one of the most memorable years of my life, surrounded by nostalgia and magic.

Michael Treloars Antiquarian Booksellers

196 North Terrace Ground floor, Adelaide SA 5000, Australia

Leave a comment